UPDATED: 5:30 p.m. ET, June 16, 2022

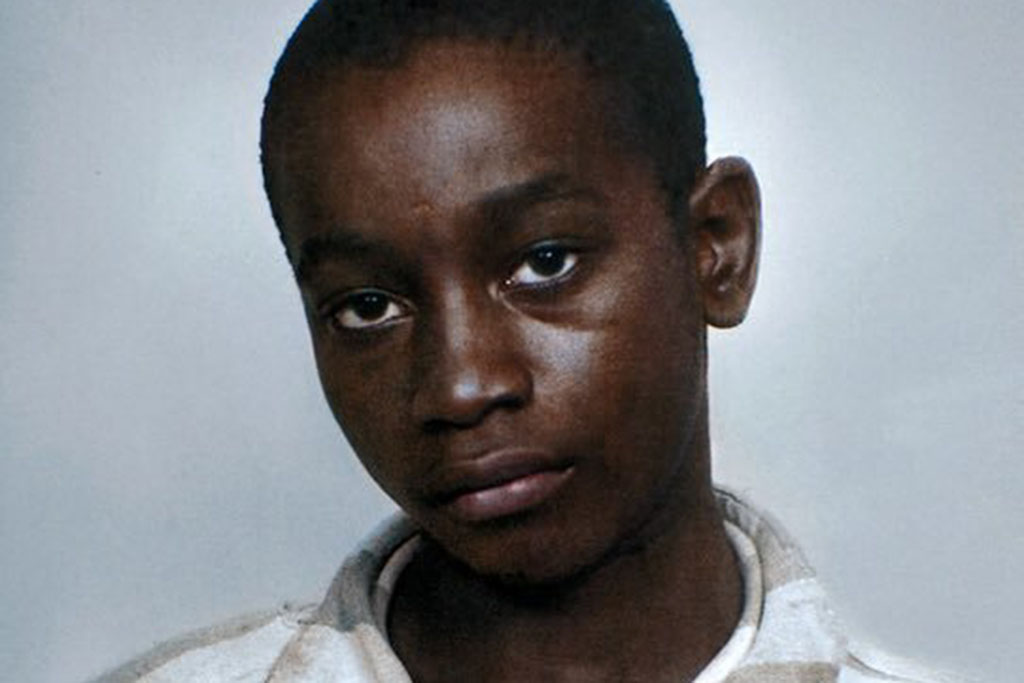

Thursday marked the 78th year since George Junius Stinney Jr., a 14-year-old Black boy, became the youngest person ever executed in the United States in the 20th century. He died in the custody of the South Carolina Department of Corrections on June 16, 1944.

The execution of Stinney, who was posthumously exonerated more than 70 years after his conviction for the murders of two white girls that he didn’t commit, forever serves as a haunting reminder of why the death penalty needs to be abolished.

What happened?

When 11-year-old Betty June Binnicker and 7-year-old Mary Emma Thames went missing after riding their bikes into town in Alcolu, South Carolina, on March 22, 1944, Stinney was arrested the following day for allegedly murdering them.

The girls had allegedly passed Stinney’s home, where they asked him where they could find a particular kind of flower. Once the girls did not return home, hundreds of volunteers looked for them until their bodies were found the next morning in a ditch.

Because Stinney joined the search team and shared with another volunteer that he had spoken to the girls before they disappeared, he was arrested for their murders.

Without his parents, Stinney was interrogated for hours by several white officers. A deputy eventually emerged announcing that Stinney had confessed to the girls’ murders. The young boy allegedly told the deputies that he wanted to have sex with the 11-year-old girl, but had to kill the younger one to do it. When the 7-year-old supposedly refused to leave, he allegedly killed both of them because they refused his sexual advances.

To coerce Stinney’s confession, deputies reportedly offered the child an ice cream cone.

There is no record of a confession. No physical evidence that he committed the crime exists. His trial — if you want to call it that — lasted less than two hours. No witnesses were called. No defense evidence was presented. And the all-white jury deliberated for all of 10 minutes before sentencing him to death.

Aimee Ruffner, sister of George Stinney, was 8 years old when her brother was arrested and found guilty. | Source: The State / Getty

On June 16, 1944, Stinney’s frail, 5-foot-1, 95-pound body was strapped into an electric chair at a South Carolina state correctional facility in Columbia. Dictionaries had to be stacked on the seat of the chair so that the boy could properly sit in the seat. But even that didn’t help. When the first jolts of electricity hit him, the head mask reportedly slipped off, revealing the agony on his face and the tears streaming down his cheeks. Only after several more jolts of electricity did the boy die.

It was, without question, one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in U.S. history.

Stinney’s case is reopened decades later

Stinney’s case was reopened in 2014 as witnesses were called to answer years-old questions. Seventy years after Stinney was executed, Judge Carmen Mullins decided to exonerate Stinney for the deaths of Thames and Binnicker, noting the teenager wasn’t properly defended and suggested his confession was the result of excessive pressure from law enforcement.

“They took my brother away and I never saw my mother laugh again,” Stinney’s sister, Amie Ruffner, who was 78 at the time, said during the trial to overturn her brother’s conviction. “I would love his name to be cleared.”

The families of the two girls opposed the judge’s decision, saying there wasn’t enough evidence to know what really happened.

Sadie Duke and Ruth Turner claimed that George Stinney threatened them and Turner’s sister, Violet Freeman, on separate occasions. | Source: The State / Getty

Yet, decades later, 27 states in the United States still practice this barbaric form of so-called justice. And the way it has been applied to our community has been especially unjust — and discriminatory.

Since 1973, nearly 50 years after Stinney’s execution, 187 people have been exonerated from death row after new evidence cleared them of wrongdoing, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Forty-one percent of those individuals were Black people.

Racial bias in death penalty sentencing

Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, says that race and other unjust factors determine who is sentenced to death.

“It’s those who are the most vulnerable,” Dieter told NewsOne in a phone interview. “If you have a poor lawyer or if you kill a White person, you’re more likely to get the death penalty. If you kill someone in Texas, it’s different than if you are accused of killing someone in another state and that is terribly unfair.”

What is even more unfair is that, since 1977, the majority of death row defendants have been executed for killing white victims, according to Amnesty International. A Yale University Law School study found that Black defendants are sentenced to death at three times the rate of white defendants when the victim is White.

Things really have not changed since little George Stinney was executed for killing two white girls based on virtually no evidence and pure racism.

Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition To Abolish The Death Penalty, told NewsOne in an interview that Stinney should remind us all that a flawed method of administering justice for the victim is not just if it clearly targets a particular group of people.

“If we don’t care whether or not race is influencing these cases, how are we going to make the system care if it turns out that our children are not getting the education they need or we’re not getting a fair shake in mortgages?” Rust-Tierney asked. “That is what this is about.”

At the time, Rust-Tierney’s Washington, D.C.-based organization played a pivotal role in helping to abolish the death penalty for juveniles in the United States with its 1997 “Stop Killing Kids Campaign” that led to South Dakota and Wyoming banning the practice for offenders under the age of 18. The U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the practice against juveniles in 2005.

Before the High Court’s ruling, however, 71 juveniles were on death row. Two-thirds of them were offenders of color, and more than two-thirds of their victims were white.

“For people of color, the criminal justice system has been designed to be about us and around us but never with us,” Rust-Tierney explained.

It certainly wasn’t with Stinney when his court-appointed attorney didn’t even care to call witnesses or provide evidence in his defense. And the justice system certainly wasn’t with his parents when a lynch mob ran them out of town, leaving their son in that South Carolina courtroom to face his fate all by himself.

The recorded affidavit of Bishop Charles Stinney, the brother of George Stinney, was played during court in 2014. | Source: The State / Getty

What good does the death penalty serve?

A good way to commemorate this poor 14-year-old boy’s short life is to take a moment to really ask ourselves why we need this cruel form of punishment, to begin with. Some will argue that if you kill someone, you should be put to death.

Well, the vast majority of convicts who are found guilty of killing someone are not sentenced to death. So why the selective application?

Is it making our streets safer?

No.

Has it put innocent lives on death row for crimes they did not commit?

Yes.

States have voted to end the death penalty to varying effects.

Just last year, Virginia abolished the practice. However, in California, the death penalty is still on the books despite Gov. Gavin Newsom imposing an indefinite moratorium on carrying out capital punishment.

Back in 2012 when California voters had a chance to cast ballots in favor of ending the death penalty, estimates projected that ending capital punishment would save the state more than $130 million per year in costs.

Greg Akili, the former Southern California field director for Safe California, told NewsOne at the time that as much as $100 million of the money saved from executions can potentially go to a crime victim’s fund to help support their cases.

“That is a better use of the money because many of the victims that we work with and who have been supporting the initiative are victims of rape and murder but their cases are not being aggressively pursued,” Akili said. “So the money that we save from executing people here in California can be used for that fund.”

George Junius Stinney Jr. | Source: South Carolina Department of Corrections

Stinney’s stolen future

We do not know what Stinney would have done with his life had it been spared. But what we do know is that the ugly, inhumane practice that took his life nearly 80 years ago is as flawed and broken now as it was back in 1944.

Currently, more than 50% of the 2,436 people on death row are Black and brown people, according to the Death Penalty Info website. Forty-one percent of them are African-American.

The racial bias that forced a 14-year-old Stinney into an electric chair 78 years ago clearly exists today.

We must not allow little George Stinney’s death to be forgotten.

It’s time to end the death penalty in America. Now and forever.

SEE ALSO:

Virginia Abolishes The Death Penalty, Advancing A ‘Fair And Equitable’ Future In Criminal Justice

Executed At 14: George Stinney Is A Constant Reminder That The Death Penalty Must End was originally published on newsone.com